We should be rethinking how we approach our end of life experience as a result of the crisis.

The crisis taking place in the aged care sector in Victoria during the second wave of COVID19 isn’t a scenario that would surprise many professionals working in the sector over the past decade. It certainly wouldn’t be a surprise to the countless individuals and family members who have found themselves moving through the physical and mental realities that the system brings to life. No, this crisis has been a long time in the making and it’s taken the tragic nudge of the current pandemic to draw into sharp focus the experience of aged care in Australia.

Before I get deeper into the causes that sit behind the current crisis, I want to be clear in saying that I deeply value and support the health care workers who are currently and always have put themselves in compromised situations when it comes to aged care. It’s a challenging environment to see the grim outcomes laid bare on our screens every evening as the news cycle rotates through. I imagine those hard working individuals who have been busting their gut to provide dignity and basic comfort to their patients each day through this pandemic, viewing these scenes in dismay, feeling that no matter how hard they try, people who they care about will get sick and many will die.

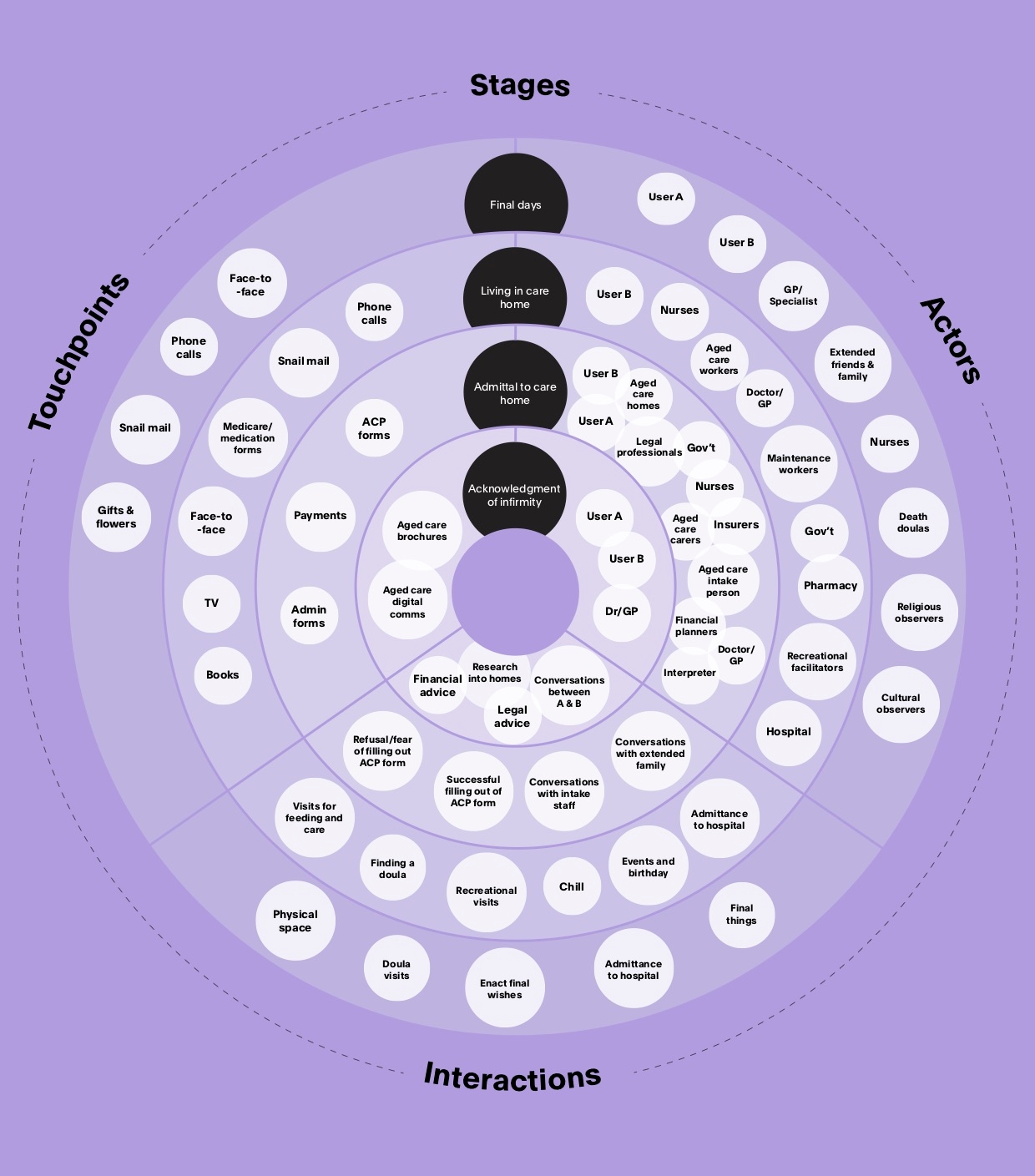

In 2018 at Portable our team released a report into death and ageing in Australia, which we later submitted to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. It was the result of an enormous amount of research into the end of life experience of people living in Australia. We engaged with not only the existing research but with people working through the various arenas of the sector through our Death Drinks, which brought together hundreds of people to talk about their direct experience. Our learnings from that work helped solidify a view that is shared by many: the relationship between the aged care sector and those who use it needs a dramatic redesign to ensure it meets the real needs of our ageing population and ourselves as humans.

The pandemic has merely highlighted that we are not set up to meet the needs of those currently using the sector. The stories of family members being told that their mothers and fathers are safe in their rooms to later learn that they have been evacuated to hospitals or have lost their lives, speak to the lack of resources and general pressure already placed upon a sector in disarray. The casual employment relationship of carers and the challenge of providing much needed training and education to the workforce that supports our elderly community highlight a system that is struggling to keep up with the demographics of an ageing population. Aged care is one of the fastest growing industries in Australia. Expenditure on healthcare will more than double per person over the next four decades. To meet the need, and just in the short term, the Aged Care Financing Authority estimates that 76,000 new residential aged care beds will be needed by 2024. The pandemic merely provides a snapshot of an inconsistent system already moving in slow motion towards generally poor outcomes for older Australians, especially those that do not have considerable financial independence.

The growth in demand alone – let alone the changes in consumer preferences, service mixes and population density – is unprecedented in Australia’s history. Yet finding the right path, establishing what options are available to us as we grow old is incredibly difficult, as highlighted in the Royal Commission’s interim report. That’s not just a result of a complicated spectrum of services, held into place by the Federal bureaucracy, but by our own limited literacy when it comes to death, end of life and care. We just don’t know what the end of life experience can and should look like. At the many events we hosted I was taken aback by the amount of people who were at once enthusiastic about talking about death and aged care but who openly admitted that it wasn’t something that they had actively planned for before. These weren’t just groups of young people keen to fill a Thursday night with drinks and conversation. Surprisingly the subject attracted a very broad spectrum of aged groups and life experience. Our online Design Your Death survey, which was one part of our research, asks people to imagine the last moments of their life. Who’s there with you? What do you regret? Where are you physically when you die? It’s not surprising that most of us imagine our later years in our own homes, with in house care, surrounded by family and loved ones. Yet this reality is out of reach for the majority of us.

Baby boomers (those born between 1944 and 1964), in general, have a greater preference for ‘ageing in place’ than previous generations. They also have higher expectations of the services they receive. Many have gone through the experience of caring for their own parents but I believe that few, if any, would have foreseen a global pandemic and the outcomes that are now emerging for many across Australia.

How do we make it better? What can we learn from what’s currently taking place?

First, we need to look more closely about how we design the end of life experience for individuals in this country. The pundits talk lucidly about the need for politicians to not waste a crisis when it comes to reform: GST, payroll tax and industrial relations reform. The pandemic provides a once in a generation opportunity to push through reforms that only a few years would have been thought as political insanity. We should be taking the same approach to aged care and end of life experience and interrogating design opportunities that sit outside the traditional conversations that end up with changes around the edges.

Korongee, Australia’s first dementia village, is due to open in Hobart this month. There are many facilities which have aspects catering for dementia patients, but this is the first to be creating an entire village, with 15 houses, a supermarket, cafe, cinema and salon. It’ll be staffed by 350 people with specialised dementia training, screened for having values that support the initiative. Applicants will be matched with housemates who share similar cultures, interests and backgrounds, using a survey developed by the University of Tasmania, and the village is being designed in consultation with the experimental MONA Gallery. Projects like these help us to see that different options are possible – how could initiatives like these be scaled across the country?

Many people in the sector talk about the promotion of intergenerational living. Could we combine student living with aged care? Can we encourage retirees to rent out spare rooms to students instead of penalising their pension for earning extra dollars? Ideas like these might have drawn skepticism from some prior to the pandemic, but surely now is the time to break free of the system that has led to the current scenarios and seriously explore newer formats and systems of care.

As we go through the following weeks and months and as the inevitable inquiries take place, we must push forward with the type of thinking that puts the actual end of life experience in the centre of discussion and reach towards outcomes that don’t simply revert back to a time prior to the pandemic, as it’s not a place anyone is championing.

Download Portable's free report 'The Future of Death and Ageing'