This is a monumental year for the internet. Forget all the daily news stories about threats to a free internet and the ever-scrutinized ethics of big tech; this year the internet turned thirty years old. That’s a milestone birthday. In particular, at thirty, you start to look back on the previous decade with a sense of growth and maturity. Consumer internet has certainly done all of those teenage things and more, and when it did turn thirty this year it was a time I started to reflect more deeply on the influence it has had on our lives and what influence it could have in the future.

It all started on the 6th of August, 1991, with this message board posting from Tim Berners-Lee which featured a short summary of a project that would become the very basis of the page you’re reading this article on now. It wasn’t much to look at back then, just text and links and academics sharing their passions, basic and simple in its design, but alive nevertheless. Looking back to those early interactions, it’s easy to dismiss the simplicity and naivety of the technology and those who were using it. Yet I’m really interested in those early days of the internet at the moment, that first decade where people from all corners of the world were rushing in, creating new businesses, new cultures and new rules that we now take as gospel as the way the internet is and should be. Amongst all of this were the debates that civil society and the media were having around all the issues, complications, and unknown side effects of a free, international meeting place that anyone could inhabit, regardless of their politics, religious beliefs or age.

One of the debates that took place early on, particularly in America, which had taken up internet usage more than any other place on earth, was how to handle all types of objectionable content on the web including hate speech and defamation, and most prolifically, porn. Porn on the internet, mainly consisting of magazine clippings and photos that were scanned and uploaded onto individual sites, was a new phenomenon and a far cry from the live streaming platforms and aggregators that are prevalent today. Parents, educators and basically anyone who had accessed pornography on the internet were concerned by the potential reach, which to that date had been restricted through media communications regulation.

The late US Senator James Exon, a socially conservative Democrat from Nebraska, was one such figure in those early debates about the internet who would later be seen as the author of many of the issues we see on the internet today. In an interview with the New York Times in 1995, Senator Exon outlined the difficulties of balancing the free space of the internet with risks of young people inhabiting the same space.

Senator James Exon:

"My major concern is to make the new Internet and information superhighway as safe as possible for kids to travel,” he said. “The potential danger here is that material that most rational and reasonable people would interpret as pornography and smut is falling into the hands of minors. The information superhighway is in my opinion a revolution that in years to come will transcend newspapers, radio, and television as an information source. Therefore, I think this is the time to put some restrictions or guidelines on it.”

In reflection, what many of us would give to have the simplicity of the problems that vaguely imbricated our lives back then.

Big tech has filled every corner of the internet we inhabit. All its ambition, confidence and grand ideals of equality and removing borders now are clearly amounting to nothing more than the type of hubris one encounters when walking into a casino. Much has been written about the threats that big tech poses to our privacy, and I don’t believe that my contribution can add any more to the level of debate that has taken place. Earlier this year I wrote about the way players like Facebook and Google are using their power to reshape the political landscape and write their own rules and histories. However, one of the more invisible stories is the eroding effect that technology companies are having on access to justice not just for minorities and those who are underprivileged, but all of us. Like the conversation about privacy, the impact is innocuous until you find yourself in the situation that thousands of people are finding themselves in every day. Unfortunately, the effects can be lethal.

In June last year, twenty-year-old Alex Kearns took his own life as a result of his experience with trading app and Silicon Valley darling, Robinhood [i]. Alex was at college after just finishing high school and had returned home as a result of COVID to live with family through the pandemic. He had around $5,000 savings and saw Robinhood as a way of experimenting with the stock market in what his parents later described as a low-risk environment. It’s not surprising that both Alex and his family felt this way about Robinhood. The app offers free sign up, and unlike many other online brokerages at the time such as eTrade, it offers no charges to buy and sell shares. It listed on the NASDAQ in June as one of the most anticipated IPOs of the year. The UI is extremely well designed, making it super easy to navigate prospective companies to trade in via tagging while allowing users to quickly enter and exit positions with a couple of swipes. Further, Robinhood does an excellent job of making the in-app experience exciting to inhabit. You need only spend a few minutes browsing the Wallstreetbets Reddit group to understand how this experience connects and feeds into the modern trading ecosystem that has emerged over the past five years for young people.

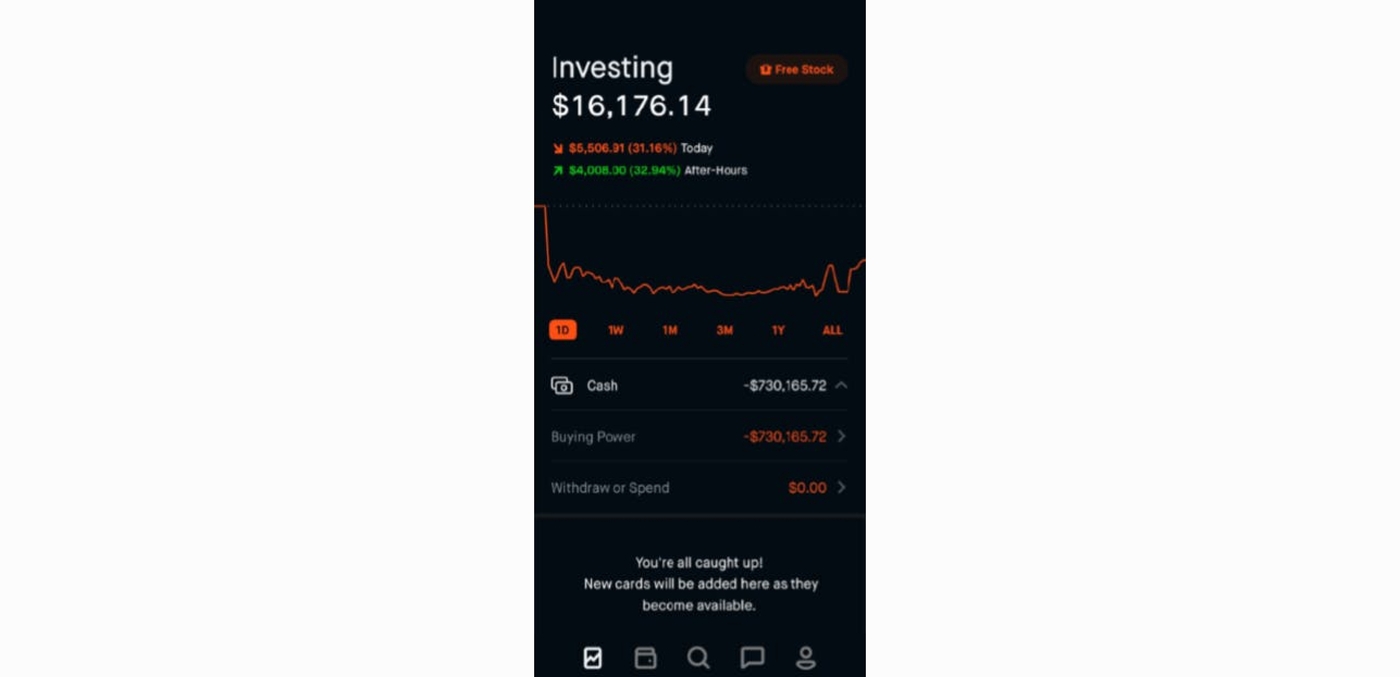

What Alex’s parents failed to understand was how this ease of use and play had led Alex to sign up for approval to buy and sell options. Options trading is a much more complicated type of trade that requires a level of sophistication and understanding that goes beyond the normal buy for a dollar, sell for two approach. It amounts to a trader making a series of bets on stocks through leveraging, which can end up with significant returns or losses. On the 11th of July Alex signed into Robinhood to find that his account was restricted due to a negative cash balance of -$730,165. Later that night, the company sent an automated email demanding Alex take "immediate action," requesting a payment of more than $170,000 in just a few days.

You only have to put yourself into Alex’s shoes for five minutes to understand the terror that he must have been experiencing from viewing the UI of his Robinhood app at that moment. Being only twenty years old and thinking that all he was risking was $5,000 of savings is a long, long way to losing twice the median cost of a house in the United States in 2020. In his mind, his immediate or even long-term future had been destroyed in the time it takes for facial recognition to sign you into your smartphone.

What I’d like to really unpick and then highlight is what happens next in this story, because my point with this case study is not how careless user interface design can kill people or that big tech should stop improving user experience. The risk that is quietly emerging day by day is that if technology companies cannot address the complaints, challenges and issues we have with using their products in a transparent, consistent, timely and fair manner, then we will find that our basic right to access to justice will exist and apply to our activities in the real world, but not in our internet lives.

Robinhood has no phone contact number, just an email ticketing system, probably Zendesk, where you submit your issue and wait for a response. Alex emailed Robinhood that day, not once, but three times, desperately seeking help with his urgent and serious issue. He did not receive a response on any of those occasions, no phone call, nothing more than a canned response:

"Thanks for reaching out to our support team! We wanted to let you know that we're working to get back to you as soon as possible, but that our response time to you may be delayed."

He tried emailing again the following day but was met with the same response, which would have left him in a state of unimaginable despair. Later that day Alex took his own life. The day after, Robinhood sent another automated message, with no sign of human inference, stating:

"Great news! We're reaching out to confirm that you've met your margin call and we've lifted your trade restrictions. If you have any questions about your margin call, please feel free to reach out. We're happy to help!"

I’ve been using Robinhood for the past seven years and although my experience is incomparable in its impact, it nonetheless highlights that this was not a one-off occurrence but part of a cultural and administrative norm at Robinhood. In 2018 I had received an erroneous six figure penalty notice from the IRS which was exasperated by the government shutdown that year. I needed financial statements from the previous year and had attempted to download them from the Robinhood tax centre, but while I could download some, the remaining few I needed would send me to their 404 page, quoting JR Tolken. I emailed support several times. I looked for a phone number to call. To this day I have not received anything more than the same canned response that Alex Kearns received.

My ticket, just like Alex’s, would have sat in a queue with possibly tens of thousands of other people’s issues which Robinhood’s team or system would have deemed as customer experience collateral damage to platform growth. If you literally cannot speak to a human to escalate your issue, to differentiate it from tax concern to mental health threat, then where do you go?

What duty of care do emerging technology companies have to the users of their services? Should they be liable if they don’t respond in a fashion consistent with what we have come to expect in the real world? In 2019 a case before the Supreme Court in the United States, led by lawyer Carrie Goldberg and her client Matthew Herrick, provided some unfortunate guidance for platforms on the internet.

In 2016 Matthew Herrick had recently separated from his then boyfriend, Oscar Juan Carlos Gutierrez, and found himself in a complicated and ultimately dangerous scenario. Matthew had ended his relationship with Gutierrez as a result of his increasingly jealous and clingy behaviour, including showing up at his workplace [ii]. What happened next highlights the complications that can emerge from the architecture of technology companies that have a consumer facing user base. As his lawyer Carrie Goldberg outlines, Matthew had been sitting in front of his brownstone apartment in New York smoking a cigarette when a stranger called to him from the sidewalk and started to walk up the steps towards him. The stranger’s tone was friendly and familiar, as if they were acquaintances, however Matthew had never met that individual in his life.

“Do I know you?” he asked, to which the man replied, “You were just texting to me, dude,” holding up his phone for Matthew to see. On the phone was a profile from dating app Grindr, which featured a shirtless picture of Matthew standing in his kitchen, smiling.

According to court filings in the United States Supreme Court, the onslaught of visitors was relentless [iii]. They would ring his buzzer at all hours, wait for him when he walked his dog, follow him into the bathroom during his brunch shifts at work, accost him at his gym and locker room, and lurk in the stairwell in his apartment building. Over the next 10 months more than 1,400 men, as many as 23 in a day, arrived in person at Matthew’s home and job. Some were innocuous and well meaning, others were not.The sheer volume of interactions had a devastating effect on his life. His ex-partner had not only put up his profile on numerous other dating sites, but in a complete disregard for Matthew’s safety, outlined to potential suitors that he was seeking fisting, orgies and aggressive sex. They were told that if he resisted, that was part of role playing fantasy that he was into and that they should just play along. It was clear that Gutierrez was using Grindr to recruit men from its platform to sexually assault Matthew. In an interview with BuzzFeed News in 2019, Herrick described his experience as a “horror film”.

“It’s just like a constant Groundhog Day, but in the most horrible way you can imagine. It was like an episode of Black Mirror… For a long time, I would ask myself, I’m a 32-year-old man, how am I a victim of this, how is this happening to me? And in those words alone there is so much blame and embarrassment in it" [iv]

In addition, Herrick’s personal data and information were also shared, along with false claims that Matthew was HIV positive. What remains unknown and frightening, according to the court filings, was that even though Matthew had closed his account in 2015, Grindr was still able to leak his geolocation data.

Without dispute, this account is harrowing on a personal and human level. Anyone would be devastated to see this happen to their family member, friend or even their worst enemy. But let’s zoom in to the interactions between the user of the platform and the platform itself. Any person in this situation would look to two immediate actions: contacting police and contacting the platform, both of which Matthew did. Herrick made fourteen police reports and obtained a family court order of protection against his stalker. But neither the police nor the courts could stop the activity. It would take months before Herrick’s stalker was arrested. Herrick and his friends filed roughly fifty reports with Grindr asking for help. Grindr was the only one that could help, was on repeated notice, and was uniquely and exclusively qualified to do so.

The only response Herrick received to his pleas for help from Grindr were auto-replies, similar to what we saw with the case of Alex Kearns. In the end, Harrick took his complaint to court where it ended up in the Southern District of New York. At the hearing, Grindr’s counsel argued that the company was not obligated to act, nor were they liable for the harm experienced at the hands of its service. And in fact, they were right. Reading through the order and opinion of District Judge Valerie Caproni, you can see the many different attempts made by Herrick’s legal council to connect the actions of Grindr both as a platform and service to Herrick’s experience [v]. All of these were ultimately made dead ends by Federal legislation.

The Communications Decency Act, passed in 1996 and championed by Senator Exon on the basis of protecting citizens from harm on the internet, gave Grindr the legal right and shield against its actions and lack thereof in Herrick’s case. This shield meant that Grindr and other platforms like it can’t be made accountable, legally or financially for the content that is uploaded by its users and the behaviour of users themselves. There is no way around it. Carrie Goldberg petitioned the Supreme Court of the United States to review the case and shine some light on how we should interpret a law written in the dial-up era of technology within the prism of modern tech behemoths. Expectedly, the Supreme Court judges turned it down [vi].

“While dating applications with Grindr’s functionality appear to represent relatively new technological territory for the CDA, past cases suggest strongly that Plaintiff’s [sic] attempt to artfully plead his case in order to separate the Defendant from the protections of the CDA is a losing proposition. The fact that an ICS contributed to the production or presentation of content is not enough to defeat CDA immunity. Rather, an ICS only loses its immunity if it assists in the “development of what makes the content unlawful" [vii]

There are two clear dimensions of exploring this scenario that we can take. One is the legal lens where we look at the responsibilities of a platform in relationship to the law. The other is the ethical responsibility of technology companies to provide platforms that are safe for the people that use them and the wider community. Exploring the legal dimension means that we need to understand why such a law operates in this particular way, especially when it was established to protect people from harmful content, not corporations. The day that the Communications Decency Act passed in 1996, Senator Exon started his speech with the following prayer:

“Almighty God, Lord of all life, we praise You for the advancements in computerized communications that we enjoy in our time. Sadly, however, there are those who are littering this information superhighway with obscene, indecent, and destructive pornography… Lord, we are profoundly concerned about the impact of this on our children… Oh God, help us care for our children. Give us wisdom to create regulations that will protect the innocent" [viii]

On that day, only half of the Senators present and less than 25% of members of the United States House had an email address, which is a testament to how new technology was for America. The Act passed, however a series of events, similar in nature to what is taking place today meant that the original version of the Act was short lived.

A year earlier, America had experienced one of its worst homeland terrorist attacks to date. Timothy McVeigh created a 2,300kg bomb made of ammonium nitrate and nitromethane and detonated it at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building just as its offices opened for the day. The blast killed 168 people, including 19 children in the daycare centre on the second floor, and injured 684 others.

Six days later, a series of anonymous posts appeared on an AOL message board advertising t-shirts with crude slogans such as “McVeigh for President” and “Visit Oklahoma… it’s a blast”. Whilst anonymously listed, the posts cited the name and phone number of Kennith Zeran, a man who had no connection to the post or the AOL platform. The posts encouraged people to get in touch and that “Ken” would donate $1 for every t-shirt sold to the victim’s families [ix]. Within a number of days Kennith started to receive abusive and threatening phone calls, which began to rapidly increase as a local conservative radio personality read the AOL messages on his show. Zeran was unable to use his telephone as threatening calls were coming through every 2-3 minutes. Eventually his home was placed under police protection [x].

AOL took the posts down after pleading by Zeran, but he still filed suits against AOL alleging that as a distributor, AOL was negligent in failing to adequately respond to the notices on its bulletin board after being made aware of them. In the same period, other internet service providers were under attack in the courts for hosting content uploaded by their users, most notably Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v Prodigy Services Co. at the New York Supreme Court, which maintained that online service providers could be held liable for the speech of their users [xi]. AOL was a big player with big influence, and internet service providers were scared.

This series of events, among many others that were taking place in these early days of internet regulation, meant that the Communication Decency Act was amended, to include Section 230 as a way of ensuring that publishers could be protected. The specific clause, called Section 230 outlines:

"No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider" [xii]

If you were to zoom out and look at the mechanisms of the CDA, you would see two complementary forces at work. Some argue that they were contradictory, that they couldn’t both exist and allow the clarity for corporations to function within the law [xiii]. However, from the vantage point of 25 years of the internet, of hate speech, revenge porn, mass trolling and the rise of Trumpism, however crude, they could have worked in tandem.

The first mechanism forces the platform to moderate and regulate its content for the protection of users of the internet from harmful content. It provides a legal basis for people who experience issues and problems online to interact with technology companies and legitimately demand outcomes that satisfy their situations, to pull down content and do it in a timely fashion.

The second mechanism provides space for technology platforms to operate from the outset, to be protected from claims that are out of their control. One would have expected that if the law operated in the way that is intended, then platforms would have explored, innovated and created solutions to satisfactorily mediate and balance this risk, project their own and their users’ interests while making a profit. But it didn’t work out that way.

Shortly after the Act passed, the first component was struck down by the Supreme Court on the basis of free speech [xiv]. That’s right, it was completely removed. However, Section 230 of the Act was allowed to remain entirely intact. Yes, the original intent of the Communications Decency Act had moralistic motivations and undertones, but it served as a means for us all to explore the architecture of the internet from a more proactive and responsible basis. This permanent and everlasting change would mean not just the removal of legal responsibilities of existing internet service providers and technology platforms to moderate content but the very concept that this was something that start-ups and new companies should even contemplate.

The technology crash of the dot com era wiped out the majority of players that were part of this landscape, and with it, wiped out the memory of conversations of this era, of the debates and negotiations. In a way, that meant that by the time Web 2.0 and the sharing economy came around 10 years later, the prevailing motto and dialect of young entrepreneurs was ‘build it, grow it and figure the rest out later’.

As I described, Web 2.0 brought on a new breed of companies who never had to think about moderation in a deeply meaningful and structurally integral way. It’s not taught in design school. It falls outside of deep technical design and exists as a problem to be solved by some other part of the design ecosystem. The Digital Millennium Act had dealt with issues of copyright, meaning that if you put up material that you didn’t hold the rights to, you could get away with it until you were asked by the license holder to take it down [xv]. This meant there were relatively no limits to what you could do with a code respiratory, a server and an interested global audience.

For this essay, I’ve steered clear of Facebook, not because I’m a closet fan but because I’m interested in demonstrating the way in which any company that is born of this culture is psychologically constituted when it comes to thinking about moderation, access to justice and responsibilities of user safety. We’ve all heard former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen testify before the US Senate that the leadership at Facebook knows how to make its products safer but has chosen not to due to an emphasis on astronomical profits instead of people. The issues at Facebook are political, cultural and complex, so much so that we could spend several hours stuck in that universe alone pondering the mind and ethics of Mark Zuckerberg. So instead, I’d like to follow the story of a new breed of company, born in the sharing economy epoch of the internet.

Airbnb was born when Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, graduates from the same design school, created the initial concept for an “AirBed & Breakfast” during the Industrial Design Conference held by the Industrial Designers Society of America [xvi]. The premise back then was pretty simple: rent your room out to people on the internet for money. The idea was hardly original. Couchsurfing emerged as a platform in 1999 for travellers to share a couch with people they didn’t know on the internet.

Everyone has been on the family vacation where the brochure turns out to faintly resemble the real experience. I was once in the South of France on a family vacation, packing our bags for our flight the following morning up to Paris. At 8pm we received a message from the host saying they had to cancel the booking due to an unspecified plumbing issue. With less than 12 hours from our scheduled stay and two kids under 3 years old, the prospect of finding a suitable alternative in September in Paris was daunting. I tried to get in touch with the Airbnb Dispute Resolution team to help me, but their response was late, poorly coordinated and nowhere near adequate. It felt like I was calling a foreign insurance company, fully outsourced and without the power to actually engage with the issue beyond citing platitudes. That was in 2015, and although my issue was trivial in the wider context of a global platform, at that time, it felt critical to me. The type of issue that a platform like Airbnb must receive day in and day out would have been routine.

Little did I know that back then, the dispute resolution team at Airbnb was still in its infancy and they were already dealing with issues well beyond the ordinary experiences of a hotel. In the platform’s early days, the founders Brian Chetsky and Joe Gebbia were the dispute resolution team at Airbnb, answering complaints on their mobile phones [xvii]. As the company scaled, it too had to make the transition from a start-up with scant resources to a publicly listed entity servicing hundreds of thousands of reservations per year. However, it’s difficult to contemplate that Airbnb did not take the issue of complaints and harm to users seriously by investing the money and resources required. They didn’t introduce a more substantially designed team and disputes operation until they had been operating for close to a decade. That’s a long time in internet years, especially when you’re a fast growing start-up.

Through the years, Airbnb CEO Brian Chetsky, at various points of Airbnb’s growth curve, has spoken about the company’s dedication to safety and trust, yet each time he has appeared to be in response to an external crisis rather than part of an innate responsibility or system design at Airbnb. The first case I recall hearing about came from a host of Airbnb who returned home in 2011 to find that a guest had ransacked her entire apartment.

“With an entire week living in my apartment, Dj and friends had more than enough time to search through literally everything inside, to rifle through every document, every photo, every drawer, every storage container and every piece of clothing I own, essentially turning my world inside out, and leaving a disgusting mess behind" [xviii]

This harrowing experience played into the fears of almost anyone who had thought of putting their apartment up for rent online before. The fact that it was so clearly detailed and took place in San Francisco, the headquarters of the company and the epicentre of Airbnb rentals, meant that many who read it had themselves rented out their own apartments and could imagine themselves in similar scenarios. Yet this incident had three clearly defined acts, the first was the incident itself, the second was the experience of connecting with Airbnb. As the host went on to outline in her blog post:

“My first call was to 911. I stood by, horrified and hysterical, as 2 officers from SFPD checked every corner, every closet with guns wielded. My next call was to airbnb.com - I tried their "urgent" line, their email address, their general customer support line. I heard nothing–no response whatsoever–until the following day, 14 sleepless hours later and only after a desperate call to an airbnb.com freelancer I happened to know helped my case get some attention. (This has been my most urgent request of the agency: that they immediately institute a 24-hour/day customer support line. A 24-hour/day business absolutely needs this in place.)"

The third part of this story was the public response from Airbnb. In what famously became known as #RansackGate, the host detailed that after she had written her account on her blog, Brian Chetsy had contacted her and rather than offering support, asked her to remove the story from her blog, saying it could hurt an upcoming round of funding [xix]. Soon #RansackGate was trending on Twitter, and the incident became an important moment in history for the company.

Chetsky responded with apologies and a ramp up of services for hosts including social identity checks and the introduction of a $50,000 “Host Guarantee” to pay for the damages experienced by a host in similar circumstances [xx]. However, the team was clearly playing catch up. The organisation had neither the institutional knowledge nor the protocols, system design or people to be able to deal with issues of this nature. It’s interesting to note that this was a “host side” issue and until that date no stories of guest experiences had successfully made their way into the public sphere.

Four years later, a 29-year-old Australian woman was on a holiday in New York and out with friends in Manhattan. She returned alone to the Airbnb she had rented on West 37th Street and hadn’t noticed anything odd or suspicious as she entered the apartment. However, as Olivia Carville, an investigative reporter from Bloomberg recounts, the young woman was met by a man with a kitchen knife who proceeded to rape her. He left, taking with him her mobile phone and other belongings. She was able to call the police who were able to apprehend the man [xxi].

This time when the woman contacted Airbnb, her matter was dealt with by an internal crisis management team. Her mother was flown out from Australia to help support her, and Airbnb secretly paid her $7 million dollars to keep the incident quiet, lest it spark media scrutiny, particularly at a time when Airbnb was in fact deemed illegal to operate in New York for this particular type of rental. Today the internal complaints team is spread across Dublin, Montreal and Singapore, but the majority of disputes are outsourced to third party teams around the world.

This is how a modern listed internet company deals with complaints on its platform. You create a small unit within your company then you outsource the bulk of the operations to other companies at a lower cost. Problems flagged by a predetermined set of rules are dealt with centrally, while those deemed to be at risk to the company’s reputation are paid off. Non-disclosure agreements are signed, and maybe people get their day in court but only if the platform you happen to be on has chosen to take accountability for their role in the matter. You are entirely dependent on the founders’ sense of what their own responsibilities to their users are, and if this comes up against larger goals such as an upcoming raise or an IPO, then the application of justice will be decided too by the intent of the founders and the culture that circles around them.

Or you are a company like Robinhood, you simply set up a ticketing system, automate relevant bulk responses and hope that services like ZenDesk and Atlassian can figure out ways that reduce the number of support people required through automation and artificial intelligence. You program the system in a way that best meets your own definition of a service level agreement. But how do you set up those rules? And how do you ensure that the legitimate issues are dealt with by the right people in the right way? What motivates you to do that? You can’t catch every ticket, there are too many users. So, you can try to do the right thing, but ultimately the legal team ends up mediating disputes in the United States where most of these platforms originate or end up. If you live outside the borders of America or the West where there is no corporate headquarters and you can’t tap into a friend in your network who happens to know someone who works at that technology company, then must you endure endless torment or personal destruction all because you signed up to an account on the internet?

If there is no law that is forcing technology companies and designers to build in protections and safeguards, should these companies even bother to deal with this problem? Currently the answer is no. Only when it makes sense. This is creating a knock-on effect where we are replicating the same crappy justice system that we currently have in the real world. If you need to wait months or years on end to have your dispute taken seriously, then the system ends up looking like what we have in the Family Court in Australia where disputes are long, costly and access to justice becomes the reward you receive as a result of endurance, or privilege, or combination of both. This erosion, like all erosions, is slow, inconspicuous to the naked eye and a by-product of both a legislative setting and a culture existing across the entire tech and design ecosystem. From the start-up founders to the venture capital ecosystem that backs them, to tech and design tribes moving from company to company selling their technical skills and systems know-how to the same C suite staff who managed the same type of problem at the previous start up, it’s not a diversity problem and doesn’t matter who you bring into the fold of your organisation because culturally it’ll be solved in the same way.

Restoration

How do we address this harm without causing total chaos to the existing internet that we know?

To start to think about how we change all of this, to redirect course, we need to imagine the internet of the 90’s as less of a wild west but as a state that was unadulterated, simple in its design and with multiple options for surfers of the web to act upon. Paradigms have been created across design, technology, customer service, dispute resolution and our own relationships and interactions with the products we use that are endlessly reproduced, leaving us all with the sense that this is the way technology is experienced and there are no alternatives. The various dimensions – the legislative, the cultural and the user centric – must all be addressed for us to move away from this sense of nihilism regarding the technology we use.

In June this year, Republican Sen. John Thune reintroduced a bill co-sponsored by a bipartisan group called the Filter Bubble Transparency Act. The bill would require large-scale internet platforms that collect data from more than 1 million users and gross more than $50 million in annual revenue to provide greater transparency to consumers and allow users to view content that has not been curated as a result of a secret algorithm" [xxii]. A second bill, called the Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency (PACT) Act, seeks to go one step further by actively stripping Section 230 protections from companies that do not take active steps to moderate their content or respond to court requests to remove harmful content.

These are starting points. They are a reimagining of human agency in a world where currently no options exist or are buried deeply in user settings none of us know exist. You might ask, well what actual effect will this have on content moderation, trolling, revenge porn and access to justice on the internet? The reason this type of thinking is important is that it starts to reintroduce to people using the internet that they have options, that they can control the way in which these platforms operate, and they too have agency in a world governed by large platforms. This type of thinking also forces these companies to not just operate a one-dimensional view of the people that use their software but as individuals with agency. This type of regulation means that legislative restraints will need to enter into the technical exploration and ultimate service design of products. It may be too late for the likes of Facebook, but it is a place to start, and will no doubt be a discussion point for the design community if these bills pass congress, which isn’t a certainty.

Another point to this is that artificial intelligence should be able to solve these types of problems. They should be able to detect patterns of miscreant behaviour. They should be able to detect when a user is citing the same geolocation data as a complaint filed earlier that week or month. They should be able to recognise the difference in context between an 18-year-old with $5,000 invested in options trading on the end of a $135,000 margin call and a 40-year-old, middle aged white guy trying to get some paperwork for a tax return. And that recognition should allow companies to think and act more comprehensively on issues of user harassment and harm.

This isn’t case at the moment, because AI and the serious engineering firepower in these companies is being used to solve problems such as efficiently displaying content and advertising that align with user data, or optimisation problems at the revenue end, not at the human end of the funnel, where we each react differently, either as benevolent participants or malicious actors.

I’m not saying let’s all sit back and wait for AI to come through and make the internet a more just place. The technology needs its own measures and set of guiding ethics to ensure we don’t harvest and amplify the same kind of prejudices and poor decision making that currently exists in the real world. Just because Airbnb possesses dispute resolution data handled in the first half of its life, doesn’t mean that it should use that data as a building block to train an algorithm to be used in the next decade. But the sheer magnitude of use taking place on these platforms, combined with the complexity of human interaction between guests and hosts, couples trying to hook up with each other, traders seeking to understand the underlying mechanisms behind their trades, and a multitude of other uses means that human intervention and outsourced dispute centres can only go so far.

From an organisational perspective, the cultural side of this equation is perhaps the hardest element for us to predict and change. Laws certainly help, but it takes leadership and hard decisions to ensure that users of a platform have a legitimate and ensuring means of connecting with the managers of a product when harm takes place. What I’d like to see from the next generation of start-ups that are pitching right now for the talent and capital to grow into tech giants, is a culture that actively pushes product development from the point of friction between the service and the people it serves. When Airbnb pitched to venture capitalist Chris Sacca in its early rounds, he famously said to Chetsky and Gebbia, “Guys, this is super dangerous. Somebody’s going to get raped or murdered, and the blood is gonna be on your hands.” He didn’t invest. The culture that we inhabit needs to press these concerns and act with questions of access to justice front of mind, no matter how seemingly twee or benign the concept. Engineering and design talent should be auditing companies upon their entry to see if the effort that is spoken to actually lines up in team structure and the deployment of capability. Investors should demand that the companies they invest in should disclose the ratio of revenue to dispute resolution spend along with significant issues with users.

My persistent view aligns with what I wrote about in our Redesigning Work publication a few years back. We are currently experiencing the crude early forms of technology platforms which are unsophisticated, brutish, and heavy handed in their management and execution. We don’t know any better because so few of us have experienced an environment that truly balances design, economics and human centred technology without leaving us feeling that we should be grateful to have something that was better than a few decades ago.

The internet evolves quickly.

One minute we’re collectively chasing Pokémon around our front lawns, the next we can hail a car to pick us up from our doorstep and track its approach on our screen. Where we direct our energy today matters. The next decade needs us to push for an internet that keeps us safe and resolves our problems at the same time.

By Andrew Apostola, CEO, Portable

If this article touches on any issues of concern for you, we recommend calling Lifeline on 13 11 14 or 1800Respect on 1800 737 732.

References

[i] “Alex Kearns died thinking he owed hundreds of thousands for stock market losses on Robinhood. His parents have sued over his suicide”, CBS News, Tony Dokoupil Et Al, Feb 28, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/alex-kearns-robinhood-trader-suicide-wrongful-death-suit/

[ii] “Herrick v. Grindr: Why Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act Must be Fixed”, Carrie Goldberg, LawFare, 14 August, 2019,

[iii] “Matthew Herrick vs Grindr LLC, KL Grindr Holdings Inc, Grindr Holding Company”, http://www.cagoldberglaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/HERRICK_SCOTUS.pdf

[iv] “A Man Sent 1,000 Men Expecting Sex And Drugs To His Ex-Boyfriend Using Grindr, A Lawsuit Says”, BuzzFeed News, Jan 10, 2019, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/tylerkingkade/grindr-herrick-lawsuit-230-online-stalking

[v] “Herrick vs Grindr, Opinion and Order”, Justia, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2017cv00932/468549/21/

[vi] “Grindr Harassment Case Won’t Get Supreme Court Review”, Bloomberg, Oct 8, 2019, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/tech-and-telecom-law/grindr-harassment-case-wont-get-supreme-court-review

[vii] “Herrick vs Grindr, Opinion and Order”, Justia, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2017cv00932/468549/21/

[viii] “The Origins and Original Intent of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act”, Christopher Cox, August 28, 2020, https://jolt.richmond.edu/2020/08/27/the-origins-and-original-intent-of-section-230-of-the-communications-decency-act/

[ix] “Zeran vs America Online Inc”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeran_v._America_Online,_Inc.

[x] “In the Pursuit of Happiness”, Kenneth Zeran, 2021, https://www.kennethmichaelzeran.com/Zeran-AmericaOnline/Zeran.html

[xi] “Stratton Oak Inc vs Prodigy Services Co”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stratton_Oakmont,_Inc._v._Prodigy_Services_Co.

[xii] “Section 230 Communications Decency Act”, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

[xiii] “The Origins and Original Intent of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act”, Christopher Cox, 27 August, 2020, https://jolt.richmond.edu/2020/08/27/the-origins-and-original-intent-of-section-230-of-the-communications-decency-act/

[xiv] “Reno vs American Civil Liberties Union”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reno_v._American_Civil_Liberties_Union

[xv] “Digital Millennium Act”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Millennium_Copyright_Act

[xvi] “AirBed and Breakfast for Connecting 07”, Core77, 10 October, 2007, https://www.core77.com/posts/7715/airbed-breakfast-for-connecting-07-7715

[xvii] “Airbnb spends millions making nightmares at live anywhere rentals go away”, Olivia Carville, Bloomberg,

[xviii] “Violated: A Traveller’s Lost Faith, a Difficult Lesson Learned”, BlogSpot, 29 June, 2011, https://ejroundtheworld.blogspot.com/2011/06/violated-travelers-lost-faith-difficult.html

[xix] “Airbnb is becoming known for property damage and meth”, Rebecca Greenfield, The Atlantic, 2 August, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/08/airbnb-becoming-known-property-damage-meth-and-zero-security/353519/

[xx] “Our Commitment to Trust and Safety”, Brian Chetsky, Airbnb Blog, August 1, 2011, https://blog.atairbnb.com/our-commitment-to-trust-and-safety/

[xxi] “Airbnb is spending millions of dollars to make nightmares go away”, Olivia Carville, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-06-15/airbnb-spends-millions-making-nightmares-at-live-anywhere-rentals-go-away

[xxii] “Thune, Colleagues Reintroduce Bipartisan Bill to Increase Internet Platform Transparency”, June 10, 2021, https://www.thune.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=0CA78D6E-C0A8-4BDB-9AA9-1900238810E5